Stay informed with free updates

Simply sign up to the Monetary policy myFT Digest — delivered directly to your inbox.

Have central bank interest rates peaked in the US and the eurozone? If so, how quickly might they fall? From around mid-2021, central banks clearly had to tighten significantly. But what they have to do next is uncertain. Whatever central bankers might say about what they plan to do, events always have the last word. If, as many now expect, core inflation falls quickly towards their target, they will have to loosen policy. While loss of credibility is damaging when inflation gets too high, it is also so when it gets too low. A return to sub-target inflation and “pushing on a string” monetary policy would be highly undesirable. The time to respond to such risks looks close — closer than central banks admit, especially given the lags in transmission of the past tightening.

Jay Powell, chair of the US Federal Reserve, and Christine Lagarde, president of the European Central Bank, have stated their plan not to ease soon. Intervention rates have remained stable for some time: the fed funds rate at 5.5 per cent since July and the ECB’s deposit rate at 4 per cent since September. Yet Powell warned this month that the mission to return inflation to its 2 per cent target had a “long way to go”. Similarly, Lagarde told the FT last week that eurozone inflation would come down to its 2 per cent target if interest rates were kept at their current levels for “long enough”. But “it is not something that [means] in the next couple of quarters we will be seeing a change. ‘Long enough’ has to be long enough.”

A reasonable conclusion from this behaviour is that, barring surprises, rates have now peaked. But central banks simultaneously stress their plan to keep them up. One justification for publicising that intention is that it is itself a policy tool. If markets believe lower rates will come soon, they are likely to bid up bond prices, so lowering rates and easing monetary conditions. Given the uncertainty on the outlook, central banks do not wish today’s tight financial conditions to be undermined in that way. They would prefer to preserve them until certain that their economies do not need them any more.

So far, so understandable. The question is how uncertain the outlook really is. The answers optimists give for the US and eurozone are different. But they come to much the same conclusion: the inflation threat is passing rather more quickly than central banks suggest. In recent analyses, Goldman Sachs economists present this case clearly.

On the US, they argue that “core inflation has fallen sharply from its pandemic peak and should begin its final descent in 2024”. They see further disinflation coming from rebalancing in the auto, housing rental and labour markets. They add that “wage growth has fallen most of the way to its 3.5 per cent sustainable pace”. In all, core personal consumption expenditures (PCE) inflation should fall to around 2.4 per cent by December of next year. On the eurozone, Goldman expects “underlying inflation to normalise in 2024. Core inflation has cooled more than expected in recent months . . . and wage growth is showing clear signs of deceleration.”

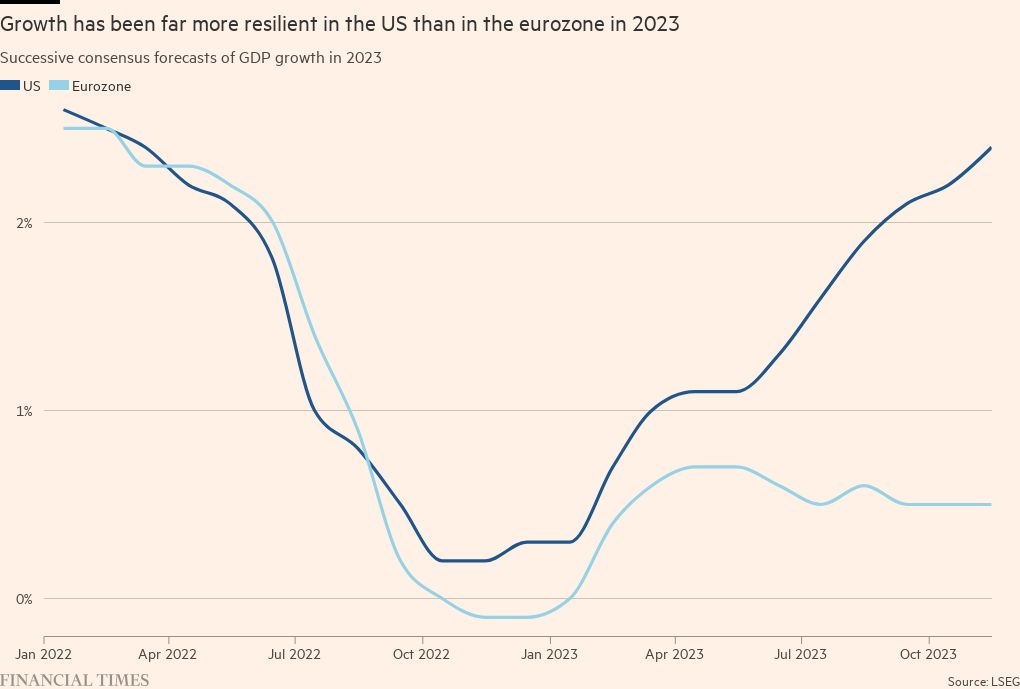

While inflation is cooling in both places, both shocks and economic performance have been very different. The most striking divergence is in growth this year. Consensus forecasts for US and eurozone growth in 2023 tracked each other closely downwards in 2022, with forecasts for 2023 tumbling from around 2.5 per cent in January 2022 to close to zero at the end of last year. But forecasts for the US are now at 2.4 per cent, while the eurozone’s are for only 0.5 per cent. The US combination of strong growth, low unemployment and falling inflation looks rather like the “immaculate disinflation” in which I, for one, disbelieved. Why that has happened is a topic for another time. In terms of output, however, disinflation looks less immaculate in the eurozone. That is not surprising, since its inflation and weak growth were powered by the energy shock caused by Russia’s war on Ukraine. (See charts.)

Now, look ahead. As John Llewellyn has argued, the US economy might be substantially weaker next year. As for eurozone growth, even the relatively optimistic Goldman forecasts are for growth of just 0.9 per cent in 2024. Moreover, even that assumes loosening of ECB monetary policy in response to better news on inflation. Central banks must look ahead and remember the lags between their actions and economic activity. In doing so, they might also cast one eye on monetary data. Annual growth of broad money (M3) is firmly negative. Monetary data cannot be targeted. But it must also not be ignored.

In brief, it looks increasingly plausible that this tightening cycle has come to an end. It also looks quite likely that the beginning of the subsequent loosening is closer than central banks are suggesting. If that turns out not to be the case, there is some risk that it will come too late to avoid a costly slowdown and even a return to too low inflation. Yet none of this is certain: policymaking is now at a truly difficult point in the cycle.

We also need to note some lessons. First, the very resilience of economies confirms that tightening was justified: how high might US inflation be now without it? Second, inflation expectations have stayed well anchored, despite the huge overshoot. Thus, the inflation targeting regime has worked well. Third, labour markets have also behaved better than expected. Fourth, forward guidance is risky: policymakers should think carefully before making commitments they might soon have to break. Finally, they should not fight a war for too long, just because they started it too late. Yes, the last mile may indeed be the hardest. But one must notice when crossing the finishing line.

martin.wolf@ft.com

Follow Martin Wolf with myFT and on X

Credit: Source link