You can enable subtitles (captions) in the video player

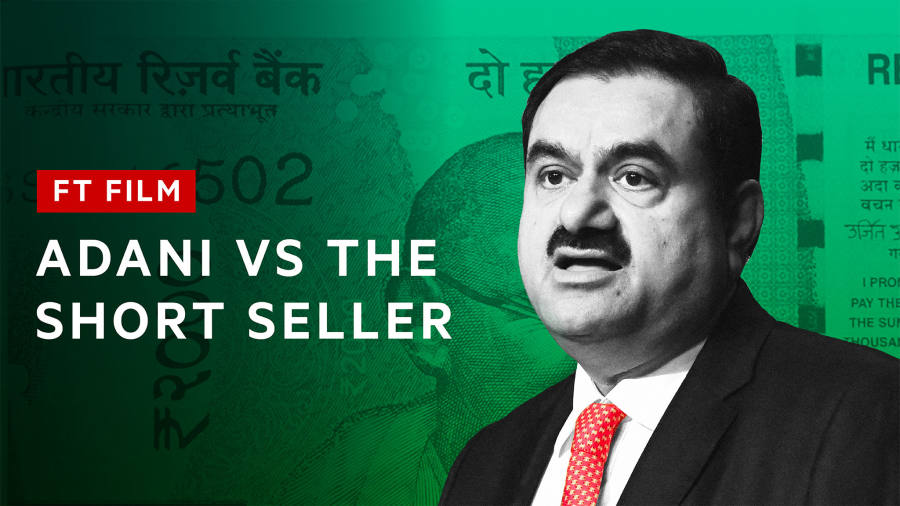

The story of Adani is the story of the world’s third-richest man being cut down to size by a short-seller group on the other side of the world.

An industrialist who has been favoured by Mr Modi.

The Adani scandal is a wake-up call to the Indian government that we need a complete overhaul of our regulatory system.

This crony capitalism has developed because these businessmen play such a key role in building out infrastructure.

The Hindenburg report threw a spanner in the works.

On January 24, a report from US-based short-seller Hindenburg Research accused Adani of share price manipulation and fraud, and that ultimately knocked about $100bn off of their market valuation.

Gautam Adani went from being the world’s third-richest man on the Forbes Rich List to somewhere in the 20s. It was extraordinary.

The Adani story is a question of who you know versus what markets know. It’s a question of whether Adani’s connections are strong enough to carry this massive infrastructure empire through the market tumult sparked by a single short report.

He has paid back his debt on his personal shareholding which he had borrowed, about $2.5bn. Nobody in this country has a concern about the ability to repay debt.

So underlying the entire story of Adani, we should never forget, is a very competent man and a very competent businessman who owns fantastic companies with very good cash flows.

The fundamentals of our company are very strong and we have an impeccable track record of fulfilling our debt obligations.

I think the Hindenburg report raised really fundamental questions about investing in India, whether you could trust the corporate governance at listed companies where you had your shares and were parking your own money. I think it also raised broader questions about the integrity of India’s institutions, whether it’s the stock market regulator, SEBI, or the law enforcement agencies. And finally, the integrity of the business press in India, the extent to which they’ve been covering diligently what’s happening at leading groups like Adani.

So, Gautam Adani, like Narendra Modi, the prime minister is from Gujarat.

He’s a first-generation businessman. Comes from a community of entrepreneurs.

He started off running his own business, then, over a period of time, got into exports.

And from then, it’s been this almost non-stop expansion.

Well, I met him in some industry forums. He came across as a very focused entrepreneur.

He’s the man who, more than anyone else, has risen both in fame and reputation during the Modi years.

There does seem to be a very, very nice parallel between the rise of Narendra Modi and the rise of Gautam Adani. And the rumours that he’s close to them are not new rumours. They’ve been around for 20 years.

Gautam Adani and Narendra Modi have a relationship that one could describe as symbiotic. Adani’s rise in business has coincided with Modi’s rise in politics, first in Gujarat, where Modi was chief minister at the same time that Adani was rising in business. And then from 2014, when Modi took power as prime minister, Adani’s rise was, if anything, even more stellar.

He has also focused his interests on those things that… what Mr Modi calls the “New India” is also focused on, which is of infrastructure-building rapidly, trying to get India up to scale so that it can compete. And on several fronts Mr Adani’s interests align with that of the Union Government of India.

He also has one other thing going for him, and that is you have to remember that he is playing on the India growth story. India needs a huge investment in infrastructure, and he is positioned right at the fulcrum where the finger needs to be put.

The deal that put Adani on the map was when he won the rights to operate the land in Mundra.

The port allowed him to demonstrate that I’m a competent businessman, regardless of any connections, which means that it opened up for him the doors to other deals.

I think Mr Adani would like the perception to remain that he is very close to Mr Modi. Now, how close he is to Mr Modi is only a question that Mr Modi could answer.

Opposition politicians and a few intrepid journalists have also been raising questions over Adani’s integrity and about possible corruption or cronyism. They don’t have much to work on other than circumstantial ties.

We don’t have any evidence of this, but there are clearly deals which make you feel that it is his closeness to the government that got him these contracts. The ports, to some extent. But the airports, for sure.

I was in Delhi, and Adani had just won the right to operate six airports all of a sudden, out of the blue. This guy was not known as an airport operator, and yet he just came in and won this massive bid.

Yes, it does help to be a big entrepreneur, because in relation to land allotment and local licencing, government steps on the plate. But they do it for everybody.

I would say that it’s worse than that. That, in some senses, the allegation has been that the state has been complicit with what has been going on with the Adani Group.

Adani has a record of winning significant court battles in India. Questions have been asked in the press about the role of the judiciary in the businessman’s rise, but nothing has ever come of these allegations, which have been dismissed by the company and the government.

The Modi government doesn’t normally comment on business stories, but it has pushed back hard on any suggestion that it has a special relationship with Adani.

Adani has been building infrastructure projects in neighbouring countries, including Bangladesh and Sri Lanka.

And, in many cases, these were deals that were agreed either during or after a bilateral visit by Modi to one of these countries. In Sri Lanka, Adani secured a $700mn container terminal project which the government said was secured with Indian government help before backing out of that statement. In Israel, Adani secured the concession to operate Haifa Port, which is Israel’s second-largest. In Bangladesh, after a visit by Modi to his Bangladeshi counterpart Sheikh Hasina, won a deal for a power project which involves burning coal in India and then transmitting power over the border into Bangladesh.

It is a structurally important business for this government for sure, because the government’s strategy of national champions is hinged on the idea that these companies provide the backbone that will take India into the next phase of its growth.

Adani, despite all of this controversy, has been able to execute these ambitious infrastructure projects. And for India to realise its demographic potential it needs infrastructure. It needs roads. It needs airports.

It needs energy. And Adani has been able to deliver that. If Adani can’t do that, then who will?

Strictly speaking, the quote, unquote, “Adani Group” doesn’t exist. That’s just the name given to the companies in which the Adani family has majority ownership. And there are a lot of them. At the heart of his conglomerate is Adani Ports and Special Economic Zone.

Adani Power is India’s largest private thermal power producer, and Adani Enterprises is the flagship company which houses Adani’s mining and coal trading operations.

Adani Total Gas is a joint venture with France’s TotalEnergies, and Adani Green Energy is India’s largest renewable energy company.

Adani’s other listed companies include Adani Transmission and Adani Wilmar. And beyond that, the group has a huge range of operations in sectors like airports, roads, and cement.

So recently the Adani Group has been on an absolute tear. It’s now India’s biggest airport operator, and last year became a media operator as well after a successful hostile takeover attempt on NDTV.

You know, the Adani business model is the same business model that is followed by many promoters in India. It’s a business model which says we get into those industries where there is a regulatory framework, where the government matters, where the politician who is in charge of the government matters.

This is not new to India. You always had business houses that have flourished by being very close to governments and have taken undue advantage of this proximity.

He has also put his money where most people have been reticent to do so. Infrastructure is a low-return, long-gestation business, and there are not too many people who are focused on it with the kind of laser-like sharpness that he has been.

Many of Adani’s listed companies had seen their share prices rocket in recent years to levels more typical of a fast-growing tech startt-up rather than, say, industrial outfits or utilities providers.

Before the Hindenburg rport, there were clearly overvalued compared to equivalent companies in their sectors. Clearly.

Valuations that out of the ordinary would, on their own, probably have been sufficient for Hindenburg to want to take a closer look.

I started to look into him, and it was incredible because it seemed that, even though he was growing so fast, and the share price of his companies were skyrocketing, and he was obviously playing such an important role for the government, and yet, no one seemed to be writing about him or notice him.

I was repeatedly struck by how reluctant brokers and analysts were about going public with their doubts about these companies’ valuations when, in private, they could be scathing. But the higher shares went, the more hesitant they became. The belief in Adani came down to two things. One, the narrative of India’s breakneck growth and his alleged connections with Modi. And for a great many investors that was enough to overpower any questions about the group’s financials.

Journalists and investors were starting to ask some questions about the valuations. There were also questions about Adani’s extensive use of offshore vehicles, and of the presence in its shareholder base of a lot of investors that were funds that appeared to be only holding Adani stock. But nobody could quite put it all together. And, in part, this was because Adani has a track record of going after critics, of taking legal action against journalists.

The last 20 years have not been very kind for the freedom of press in India, and one of the reasons they have not been very kind is, like in other parts of the world, more and more of the press is now being controlled by billionaires who own these press vehicles. And the reason they like to own these press vehicles is, firstly, they make sure that any criticism of them and their businesses are muted. Secondly, it’s a way to curry favour with politicians.

It was a Friday, I had just been to a work lunch, and I get a text from a contact saying, we have something that we think will be of interest to you. Do you want to take a look?

So I checked the report and, of course, the first thing that you see is how the world’s third-richest man is perpetuating the biggest con in corporate history. As a reporter, as anyone, that sort of grabs your attention.

There are two main allegations made by Hindenburg, one of which is stock market manipulation. And the other one is accounting fraud. There were all these offshore entities, a lot of which were registered in jurisdictions like Mauritius or Singapore, which only seemed to invest in Adani shares.

The Hindenburg report came out of nowhere. It stunned the markets, the business community, and India’s political class.

What Hindenburg did that was so effective was to bring all the facts, all the rumours, all the circumstantial evidence together in one place and turn it into a narrative that was credible.

Jugeshinder Singh, one of Adani’s senior executives, came out with a video that hit back aggressively at Hindenburg’s claims.

The report is a malicious combination of selective misinformation, stale, baseless, and discredited allegations that have been tested and rejected by India’s highest courts.

Adani came out with a 413-page rebuttal which was quite extraordinary. What struck us at the FT was the rhetoric that was used in it. They called the report “a calculated attack on India,” which seems like a strange language for a company to be using and is more reminiscent of the kind of rhetoric that you hear from India’s government.

The report also unleashed an outcry in parliament. One of the loudest voices was Mahua Moitra, a former banker from the Trinamool Congress party. She had been urging the market regulator to investigate Adani’s alleged market manipulation.

Some of the issues he raised were issues that I had raised, were issues that other people had raised over the last three or four years. And some of what Hindenburg pointed out was just common sense and logical.

At one point, Rahul Gandhi, who’s the most prominent figure in the opposition Congress party, stood up and gave a speech questioning all of Adani’s foreign deals. He also held up pictures showing Adani and Modi sitting together on Adani’s jet. It’s very telling that all of his remarks in the speech relating to alleged ties between Adani and the prime minister were expunged from the parliamentary record.

All this is to distract from the panic that the prime minister is feeling that his relationship with Mr Irani is going to be exposed.

Gandhi was convicted of defamation in a Modi-related case in Gujarat in March, and then expelled from parliament just a year before the next election in a move that his Congress party have described as tit-for-tat retaliation against his public remarks about the prime minister and the billionaire.

Because this government functions with a level of opacity which is not normal for most democracies, and certainly doesn’t pass the smell test.

I think the opposition was always aware of just how this government was helping its friends and their allies. But given that the BJP government came to power in India on an anti-crony capitalism wicket, for them to be embroiled in a scandal that was so obviously crony capitalistic, and that too for just one man, I think that’s… all the ingredients were in for this very exciting political, financial potboiler.

I just remember checking in at the open, day after day, just watching the market value of these companies evaporate.

Indian promoters have been very good at managing the regulatory environment as a group so that short-selling in India is not a frequent occurrence.

It’s not that it’s impossible to short shares or to short companies in India. It’s that it’s almost impossible to make money from it. You have to do it through other jurisdictions. The one that is most used is probably Singapore.

Hindenburg could have bet against Adani through India’s main stock index, the NIFTY 50, in which Adani companies are constituents. It would have been able to use a derivative called a “single stock future” that would allow the firm to have a weighted exposure to the group through the Singapore exchange. To do this, it would need Singapore-based banks to act as counterparties.

They would offer a security based on the whole index with exposure to India’s 50 leading stocks, but then sell most of the underlying shares, leaving just Adani companies. That means Hindenburg could have exposure to Adani and short this derivative like a normal security. Only, crucially, it could do it in Singapore and therefore avoid India’s disclosure rules that make shorting hard.

The timing of the report was pretty much perfect as far as Hindenburg was concerned. It was a surgical strike. The impact was to torpedo shares in Adani companies just as it was trying to get this massive share sale out the door.

In January 2023, Adani Enterprises launched a share offering with the aim of raising $2.5bn.

They ultimately decided to call it off. That was, I think, a huge win for Hindenburg.

If he had managed to pull off that share offering it would have been a sliding doors moment. But instead, it went seriously wrong.

And some people say because he’s a short-seller you should not trust him. I say, because he’s a short-seller, I trust him more. Why? They are putting their money where their mouth is.

There are three key elements to Adani’s finances and why Hindenburg was interested in the company. Share price, corporate governance, and debt levels.

You had Adani and his family officially holding the majority of his stock, in some cases, right at the 75 per cent limit allowed under Indian securities law. But you also had these offshore entities owning Adani shares, and these offshore entities allegedly had links to the Adani family. That raises two immediate problems. One, does Adani have a sufficient free float, and two, is there round-tripping? Is there market manipulation that is impacting the share price? Both of these could be a violation of Indian law.

So this is something I flagged way back in 2019. I wrote to the Securities and Exchange Board of India. I wrote to the Ministry of … Minister of Finance. And I got absolutely no answers.

Probably what is so distinctive about Adani is not that he engaged in these practises, that’s normal in India for most promoters, but that he did it to this level where the free float was so small, where his own ownership of the stock was so high.

In an interim report released in May, a panel asked by the Supreme Court to look into potential regulatory failure relating to Adani said that SEBI had hit a wall in its investigation, but it said the regulator had found no evidence of share price manipulation. And with no indication that the authorities are going to find a smoking gun of any kind that might back up Hindenburg’s allegations, the share prices of Adani’s listed companies have started to rise again.

The company has also taken steps to improve its opaque financing and corporate structure. The promoters have paid off a significant amount of the share-backed debt criticised by Hindenburg and brought in new investors to reduce the share of Adani companies under family control. Florida-based GQG invested almost $2bn in March and has since increased its investment. Two further listings are planned at Adani companies, worth billions.

A cleaner balance sheet and new equity financing has gone some way to reassure banks, bondholders, and investors that the company is fundamentally sound.

If you look back 25, 30 years, in every country you find very aggressive entrepreneurs coming, borrowing money, growing empires. And many of them make mistakes. They don’t build solid businesses, and when the market turns, we see them coming down. This happened in India. It’ll happen again. The key point is we must distinguish between the stock price for all these people and the businesses.

But convincing sceptics and political opponents is going to be a much tougher task.

The Adani story has revealed a lot about Indian democracy because democracy is not just living in a free country. It’s living in a country where the pillars of democracy all work together.

The image of India and Indian business has definitely taken a slight hit with the Adani group. No doubt about that. Having said that, because the India growth story is so strong, it has now become a must-win market for every company in the world.

I think it’s probably too early to say whether this story of the short seller versus the billionaire is something that has transformed Indian business, or that we will have forgotten about in a year’s time.

The issue is about the concentration of wealth and whether or not India’s middle class will rise up with the success of these businessmen. Is it going to be like in South Korea where the chaebol helped lay the foundation for the economy? Or is it going to be like Russia, where the wealth stayed in the hands of a very few oligarchs at the expense of the nation?

Credit: Source link