The far-right Alternative for Germany will push for a Brexit-style referendum on membership of the EU if it comes to power, its leader Alice Weidel said, hailing the UK’s exit from the bloc as “dead right”.

“It’s a model for Germany, that one can make a sovereign decision like that,” she said in an interview with the Financial Times.

Weidel, party leader since 2022, said an AfD government would seek to reform the EU and remove its “democratic deficit”, including by curbing the powers of the European Commission, an “unelected executive”.

“But if a reform isn’t possible, if we fail to rebuild the sovereignty of the EU member states, we should let the people decide, just as Britain did,” she said. “And we could have a referendum on ‘Dexit’ — a German exit from the EU.”

The idea breaks a big taboo in Germany, where mainstream parties are devoutly pro-European. Also, the German constitution places tight restrictions on national plebiscites, and even if one were to be held, polls suggest a large majority of Germans would vote to remain in the EU. However, among AfD voters support for the EU is weakest.

Weidel was speaking against the backdrop of a big surge in support for the AfD, which is at 22 per cent in the polls — ahead of all three of the parties in chancellor Olaf Scholz’s shaky coalition, the Social Democrats, Greens and liberals.

It is expected to win crucial elections in September in the eastern states of Saxony, Brandenburg and Thuringia — though with all the other main parties refusing to strike coalition deals with the AfD, its path to power is unclear.

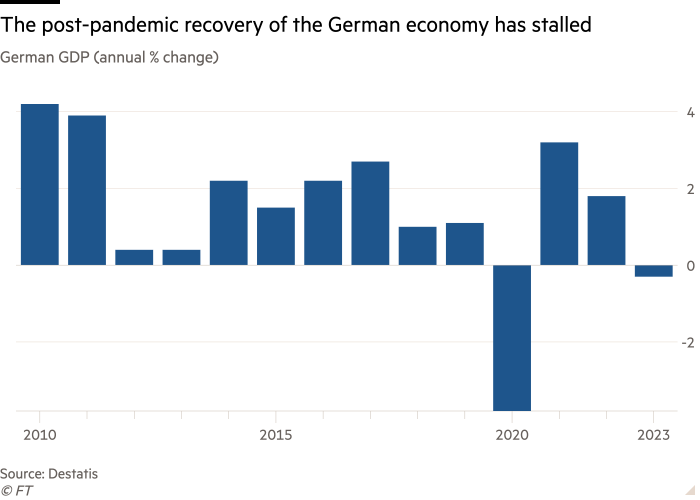

Germany’s domestic intelligence agency has designated large sections of the AfD extremist and has put several of its officials under surveillance. Still, the party has benefited from public anger with Scholz and his poor management of a worsening economy.

But in recent days it has found itself at the eye of a storm over reports of a controversial meeting last November between AfD lawmakers and the Austrian far-right radical Martin Sellner that discussed a “remigration” plan to forcibly remove millions of people with an immigrant background from Germany — including citizens holding German passports.

Anti-AfD demonstrations have been held in a number of German cities, with politicians sounding the alarm of the danger the party poses to Germany’s democratic institutions.

Weidel did not participate in the meeting and quickly fired a close aide who had been in attendance. Still, she has struggled to contain the backlash. Lars Klingbeil, leader of the Social Democrats, accused her of playing down the deportation plan and instead lashing out at a “media smear campaign” against the AfD.

“You are a wolf in sheep’s clothing,” he told her during a Bundestag debate last week. “But I’m telling you: your facade is beginning to crumble. People are finally getting to see the real face of the AfD.”

In her interview, Weidel blamed Correctiv, the investigative outlet that first reported the meeting, condemning the organisation’s methods as “scandalous”.

“It was just an attempt to criminalise the very idea of repatriating people lawfully who don’t have leave to remain here, or are subject to a deportation order,” she said. “The AfD is the party that stands for enforcing this country’s laws.”

She said that for her, the concept of “remigration” meant expelling people who had “illegally acquired citizenship under false pretences”, or individuals “with dual nationality who are suspected of terrorism, or are convicted criminals”. She ruled out mass expulsions. “You can’t generalise here.”

But she also said that the 1.1mn Ukrainian refugees currently in Germany have no long-term future in the country, adding it had been a mistake to let them draw welfare payments. “It’s clear that when the war ends, all Ukrainians will have to go home. They will be needed anyway to help rebuild their country.”

The AfD was set up in 2013 by conservative economists angered by the eurozone bailouts during the sovereign debt crisis. But it gradually shifted rightward, riding a wave of anger at former chancellor Angela Merkel’s open-door refugee policy to forge a fiercely anti-immigration, anti-establishment platform.

Weidel, who has a Ph.D. in economics and worked for Goldman Sachs and Allianz Global Investors before entering politics, has led the AfD’s parliamentary group since 2017. In a civil partnership with a woman from Sri Lanka, she stands out in a male-dominated party with traditional family views.

With her trademark white blouse and pearls, well-to-do background and career in finance, she lends the AfD “an aura of bourgeois respectability that has strong appeal for middle-class voters beyond its traditional hard-right base”, said Hans Vorländer, a political scientist at Dresden Technical University.

Yet security officials warn that behind that image lies a party has been heavily infiltrated by right-wing extremists and is becoming increasingly radicalised. A German court ruled in 2019 that one of its most senior politicians, Björn Höcke, can be described as a fascist, citing “verifiable facts”.

Other parties have responded to the AfD threat by constructing a “firewall” that precludes any form of coalition or co-operation with the party. As a result, despite its strength in the polls, the AfD does not rule in any of Germany’s 16 state governments.

Speaking from her office overlooking the Reichstag, with the noise of anti-government protests audible in the distance, Weidel herself acknowledged that the AfD would not come to power in Berlin “before 2029”.

But she insisted a future role for the AfD in government was “inevitable”, predicting that the centre-right Christian Democrats (CDU) would be the first to abandon their boycott.

“The CDU won’t be able to maintain its firewall in the long term,” she said of the party once led by Merkel. Elections in the central German state of Hesse last year had shown “that we can form a clear right-wing majority. And the CDU can’t refuse to accept that in the long term, especially in the eastern states.”

Asked what the AfD’s top priorities would be in government, Weidel said it would “introduce effective border controls . . . and immediately deport foreign criminals”.

It would reform the tax system, slim down the state and end Germany’s shift away from fossil fuels to renewable power. “France is planning 15 new nuclear power stations and we’re betting on wind turbines and solar panels that we can’t even make ourselves.”

Credit: Source link