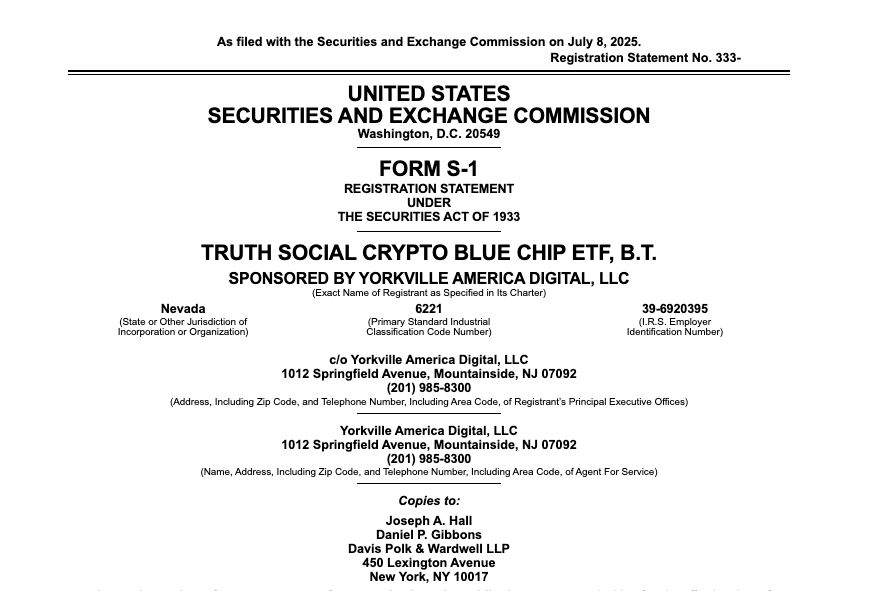

Just Stop Oil protestors tried to disrupt the cricket match between England and Australia earlier … [+]

Getty Images

Last weekend, a Californian entrepreneur who helped to raise funds for the organization that gave birth to the protest group Just Stop Oil told a newspaper that he now believed the group’s initiatives, which include disrupting leading sporting events as well as blocking roads and bridges, had become counter-productive because they alienated would-be supporters. Unsurprisingly, the group rejects the charge, arguing that its research suggests that its actions led to increased support for moderate climate groups.

The dispute comes at a time when research from academics at HEC Lausanne, the Faculty of Business and Economics of the University of Lausanne, suggests that attacks on companies by environmental activists not only change the behavior of the victims of the attacks but also that of their rivals.

ADVERTISEMENT

In an interview to discuss the study, Firms, Activist Attacks, and the Forward-Looking Management of Reputational Risks, one of the authors, Jean-Philippe Bonardi, said that because competitors anticipate they will be next in line and therefore change how they do things “the impact of activists is bigger than people think.” Bonardi, a professor at HEC Lausanne, as well as a co-director of the Enterprise for Society (E4S) Center, which funded the research, added that, as such, activists could play a big role as a sort of watchdog or regulator.

However, he also pointed out that the picture was quite complex for a number of reasons. For example, it was hard to say whether activism was a truly efficient mechanism for regulating behavior because the groups might not necessarily target the worst offenders. In the interests of raising awareness of their own “brand,” for instance, they might focus on a company that, while not a significant polluter, was well known.

Another issue was that companies might not respond as expected to the attacks. Indeed, the study, which was co-authored by Estefania Amer, found that two kinds of firm typically didn’t respond. The first included those that were poor performers in environmental terms and for which fixing the problems would be considered too costly. The second was composed of those that were already quite good and would therefore not see much benefit from making changes.

ADVERTISEMENT

The companies most likely to respond were typically in the middle in terms of their environmental behavior. Activists understood that and therefore targeted them, explained Bonardi, adding that they were also “very strategic” with regard to which companies they chose to attack and what they asked them to do.

On top of that, chief executives — if they responded to the attacks at all, which was rare — were more likely to use facts and measures rather than really engage with their critics. For example, after Greenpeace activists climbed the Deutsche Bank headquarters in Frankfurt ahead of the annual shareholder meeting of its asset management company DWS executives simply issued a statement saying DWS, which disputes claims it misled investors over “green” investments, agreed with Greenpeace that climate change required drastic action but disagreed on how to get there. This cautious approach was “another reflection of it being a tricky game,” he said.

Although the paper did not look at the role of the media, Bonardi points out that even the way that campaigns are reported can be significant in determining their success. This can be particularly true if an attack involves — as has been the case recently — a big sporting event because such occasions are also important for the media.

ADVERTISEMENT

Bonardi and Amer acknowledge that more work needs to be done — particularly in the area of the different stances on environmental and other environmental, social and governance (ESG) matters of different managers within businesses. But their report does point to the potentially important role being played by activists — along with investors — in changing corporate behavior and attitudes in this area.

Credit: Source link