As the U.S. workforce diversifies in age, HR leaders are challenged to create policies and practices that appeal to five highly distinct generations. One segment in particular—older workers—will be increasingly represented in the workforce in the coming years. Yet, recent research has found that many employers are not offering environments conducive to recruiting or retaining these professionals. Without strategic planning now, they say, systemic ageism in the workplace could cause employers to miss out on the potential of this growing population of workers.

According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, those over age 65 will comprise about 8.6% of the U.S. labor force by 2032—up from 6.6% in 2022, accounting for nearly 60% of the overall growth of the labor force during this timeframe. Two years ago, about 19% of Americans age 65 and over were working, a figure that the BLS expects to jump to 21% in the coming years; labor force participation rates are expected to flatline or drop for all other age groups, except the 55-to-64-year-old population.

Stacie Haller, chief career advisor at ResumeBuilder, says a “mixed bag” of factors keeps Americans in the workforce longer today—from living longer, healthier lives to financial concerns. She adds that the rise of work-from-home and part-time, non-traditional roles are also contributing.

According to Richard Wahlquist, CEO of the American Staffing Association, their employment can be a boon for organizations, particularly in a tight labor market.

“Experienced workers bring a wealth of knowledge, institutional memory and proven skills to the table,” he says. “Studies show age-diverse teams are more innovative and productive.”

But are employers prepared to take advantage of these opportunities? According to new research from ResumeBuilder, many aren’t. The organization found, for instance, that 42% of hiring managers surveyed said they consider age when reviewing resumes, and one-third acknowledge a bias against senior candidates.

Of the hiring managers surveyed by ResumeBuilder who admit age bias against older workers, three-quarters say that view is motivated by that population’s proximity to retirement. In contrast, nearly two-thirds say they are concerned about workers’ potential health issues. Almost half cite worries about older workers not having enough technology experience; just two years ago, that figure stood at 37%, suggesting rapidly advancing technology could accelerate ageism in the workplace.

Age discrimination isn’t “just unfair, it’s bad for business,” Wahlquist says.

“Ageism leads to a loss of talent, decreased employee morale and even potential lawsuits,” he notes. “We really need to have a paradigm shift in terms of perceptions of older workers.”

The concept of ageism in the workplace isn’t a new one; yet recent advancements in corporate diversity, equity and inclusion agendas don’t seem to have moved the needle forward much for older workers.

For instance, a 2022 i4cp survey conducted in partnership with the Age-Friendly Institute of global workers over 50 found that 70% said they have experienced ageism in the workplace. Of those, 70% have seen employers give high-visibility projects to younger employers, while more than half reported older workers have been targeted for layoffs. More than 40% said leadership has tolerated or ignored ageism.

While ageism can crop up throughout the employee lifecycle, hiring is often where it is most visible and impactful.

More than 40% of hiring managers surveyed by ResumeBuilder say they’re less likely to hire a candidate who presents to a job interview with an “elderly” appearance; more than one-third of them suggest older candidates should attempt to look younger when interviewing.

Of hiring managers who say they consider an applicant’s age in the hiring process, almost half evaluate the candidate’s appearance from a photo; nearly as many hiring managers contend LinkedIn contributes to age bias in the hiring process. More than 80% gauge the candidate’s age by considering their years of experience, while almost as many rely on the year the candidate earned degrees.

Haller said she recently spoke to an older job candidate who reported sending hundreds of applications without a single response. “The minute I looked at the resume, I knew why,” she said, noting that some resumes may have red flags that could set off age bias among hiring managers and recruiters—such as decades-old experience or an AOL email address.

“Some older workers may not realize what’s hurting them on their resume. There needs to be more understanding on both ends,” she says, noting that since HR typically is the first point of contact with candidates before they connect with hiring managers, HR has to “set the stage in initially screening candidates.” For instance, job application forms should be restructured to prohibit asking for college graduation dates.

“[Hiring professionals] need to acknowledge that many older folks want to work and have a lot to contribute, and maybe they just don’t know how to put together a current resume,” Haller says. “So, get over it.”

That mindset shift must start at the top, she adds.

Yet, despite research that shows candidates, employees and hiring managers acknowledge ageism in the workplace, leaders are still lagging behind on this recognition, according to i4cp. In a recent study of more than 275 business and talent leaders, 80% of respondents said their firms value every employee solely based on qualifications, while 60% purport to have cultures affirming older workers’ value. Less than one-quarter think older workers are promoted at a lower rate than other employees, and just 15% say older workers are less likely to have access to high-visibility projects.

“If age bias is happening in an organization, its root source must be identified and addressed as a strategic imperative for the business. Because it is,” says Lorrie Lykins, vice president of research at i4cp. “This is about the culture of the organization, and everyone is accountable for that. Of course, there are risk management concerns, but it must start with the culture, and this is set at the top of the house.”

Getting proactive about addressing age bias

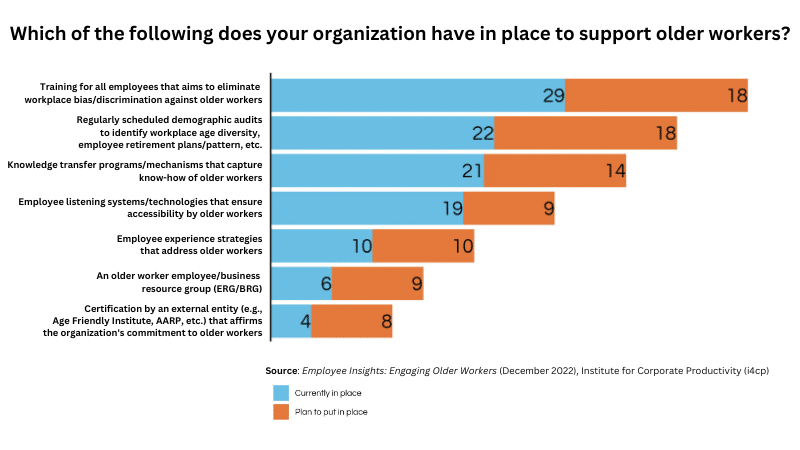

In its survey of business and talent leaders, i4cp found that training to eliminate bias against older workers was the most common effort to confront ageism in the workplace—but still, just 29% of those surveyed have such training, with 18% planning to launch it. Other common strategies include demographic audits and knowledge-transfer programs.

Just 6% have an employee resource group for older workers, and only 4% have received certification from an external agency like the Age-Friendly Institute or AARP.

In addition to advancing these efforts, i4cp recommends taking a broad lens when tackling ageism in the workplace; for instance, making age diversity a priority in strategic planning and conducting a full audit of talent practices to root out bias.

“Ageism appears in a lot of ways: syntax in job descriptions and postings, the makeup of interview panels, promotions, performance reviews, high-profile project assignments, recognition—both formal and informal—ageist jokes in casual banter and so much more,” says Lykins. Some forms of ageism may be less apparent, such as coded language.

“Ageism appears in a lot of ways: syntax in job descriptions and postings, the makeup of interview panels, promotions, performance reviews, high-profile project assignments, recognition—both formal and informal—ageist jokes in casual banter and so much more,” says Lykins. Some forms of ageism may be less apparent, such as coded language.

“Words and phrases like ‘overqualified,’ ‘overly credentialed’ or ‘not a fit for the high-energy culture’ are red flags,” she notes.

Apart from evaluating talent practices for such problematic signs, i4cp recommends employers aim to create lasting relationships with older workers. These can include phased retirement options, part-time work for retirees and alumni networks.

Wahlquist adds that training and development opportunities that are equally accessible to all workers can also be an important tool. Mentorships, for instance—both traditional and reverse, where younger workers mentor older workers—can “take the friction out of bringing all of these different generations together in the workforce.”

Listening to what older workers want

Any talent strategy must be aligned with workforce needs—and that extends to older workers. It’s key, Wahlquist says, for HR to understand what motivates older workers—and candidates—and to use that information to tailor talent practices.

It’s an approach that i4cp has found is largely lacking. For instance, just 15% of employers surveyed believe older workers want predictable schedules, but one-third actually do. Meanwhile, nearly 60% of leaders think older workers want a job with comprehensive health benefits, but that’s actually only important to 26% of older workers surveyed.

The research found that older workers are most drawn to jobs that offer competitive wages, flexibility, the ability to work remotely and a positive culture. Meanwhile, according to i4cp, the top factor driving older workers to continue working past retirement age was financial pressure, closely followed by a desire to remain mentally sharp.

“We need to be allowing older workers to showcase their abilities as opposed to making judgments about what they want or can do based on our own personal experience,” Wahlquist says. “Everybody is capable of learning, stretching and growing at all ages.”

He adds that the rise in skills-based hiring will be an important tool in helping older workers realize that aim. Wahlquist notes that members of the American Staffing Association have increasingly worked with candidates to analyze their skill sets and help showcase those—and not their age-identifying experiences—to employer clients.

“We have to be reviewing hiring practices to make sure we’re focused on skills and qualifications,” he says. “When you focus on skills-based hiring, it clears forms of clutter that can result in unconscious—and sometimes conscious—bias.”

Particularly as more employers strive to be considered diverse and inclusive, allowing ageism to permeate can position the organization and its culture as inauthentic, Lykins says.

“And what everyone wants is authenticity—especially the talent we want to attract and keep.”

Credit: Source link