A simple statistic shows why mining group Rio Tinto has set its sights on becoming the next king of copper: an electric car needs 42kg of the metal — almost three times more than a traditional combustion engine vehicle.

This has helped dub copper “the metal of electrification” with demand expected to double to about 50mn tonnes annually by 2035 as the world transitions to cleaner energy for cars and industry, according to Wood Mackenzie.

However, the consultancy also forecasts demand for the metal is likely to outstrip supply as soon as 2026, prompting miners such as Rio to re-evaluate their long-term strategy for copper.

“I think there are new frontiers we’ve got to try,” Dominic Barton, chair of the Anglo-Australian group, told the Financial Times in Ulan Bator, the Mongolian capital.

Rio, which derives the majority of its profit from iron ore production, is considering more spending on exploration and processing of copper. It is also developing new technology to extract metal discovered decades ago but thought too deep or risky to mine.

Some of the world’s biggest mining groups, such as Australia’s BHP, Swiss-based Glencore and Newmont of the US, are also weighing up plans to expand their production of copper, which is used in car batteries, electric motors, charging infrastructure and underwater cabling to supply power to homes.

This has been a big driver of increased merger and acquisition activity this year, including deals such as BHP’s $6.4bn acquisition of Oz Minerals, Glencore’s thwarted bid to buy Canada’s Teck Resources and Newmont’s $19bn purchase of Australian-based Newcrest.

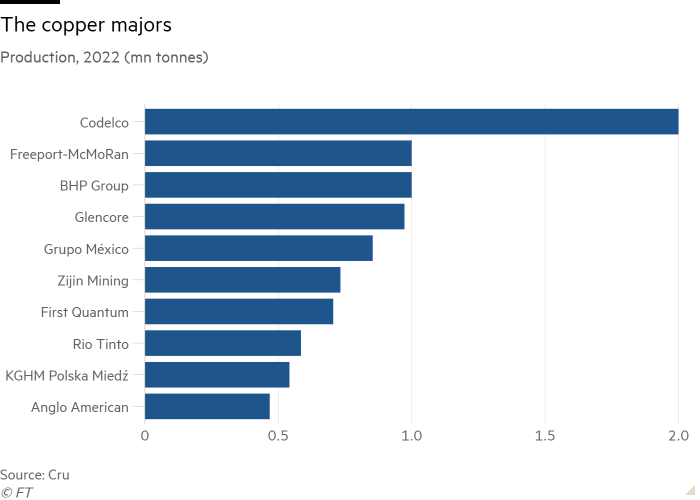

Rio is the world’s eighth-largest miner of the metal, behind copper giants such as US-listed Freeport-McMoRan and Codelco of Chile.

But of the leading groups, analysts say Rio is well positioned to expand its operations in the metal.

Rio forecasts it will meet a quarter of the global demand growth for copper over the next five years from its mines in Chile, the US, Australia, Peru and Mongolia.

Its Kennecott copper mine in Utah produces 150,000 tonnes a year. It also has a 30 per cent stake in the world’s largest copper mine, Escondida in Chile, which is majority owned by BHP with a 57.5 per cent holding. Japan Escondida has a 12.5 per cent stake.

Meanwhile copper production is expected to grow at its Oyu Tolgoi mine in southern Mongolia as the deep underground section, which has higher grades of ore than its open pit, is developed.

RBC analyst Tyler Broda said Rio’s expanding copper production would help to compensate for lower earnings from its iron ore division. Many analysts expect iron ore prices to fall in coming years.

By 2027, Rio’s earnings from copper could be about $6bn, up from $2bn this year, according to Broda’s model, largely because of expected increases in the price of the metal. By contrast, earnings from iron ore will fall to $11bn by 2027 from $16bn today, he said.

“The quality of Rio’s copper portfolio is improving, particularly as Oyu Tolgoi comes online,” added Broda. “It puts them in a bit better stead than some of their peers.”

However, Rio, like its rivals, is not immune to broader problems facing the industry. The Resolution copper mine in Arizona, a joint venture between Rio and BHP, has failed to gain permission to proceed despite attempts for years.

Analysts also say the number of projects at or near a final investment decision from mining companies is lower than historical averages as hurdles to developing new copper projects increase.

Eleni Joannides, copper research director at Wood Mackenzie, points to a plethora of risks, including new governments in important mining regions, potential changes to tax and royalties, and uncertainty over permits.

“Given the seven-to-10-year lead time it takes to bring on projects, mining companies need to continue bringing projects through the development pipeline,” she said.

Against this backdrop, Bold Baatar, the Mongolian who heads Rio Tinto’s copper business, said upfront costs would increase as miners have to work at deeper and deeper levels to find and extract higher-grade copper.

“Naturally, that better grade offsets the cost curve position. But nevertheless, the upfront capital is very hard,” he said.

At the Oyu Tolgoi operation, which is expected to deliver about half a million tonnes of copper annually by 2028, making it the fourth-biggest copper mine in the world, the company says block caving is crucial to profits.

This involves mining beneath the copper ore body, rather than adjacent to it and allowing broken ore to collapse into pre-constructed tunnels, which can then be extracted and taken to the surface.

“You’re trying to maximise the resource output, but it also enables a cheaper cost operation,” Bold said in an interview at the mine.

Bold is also cautiously optimistic about a newly developed hydrometallurgy process used to separate and extract the metal from other substances in the ground that Rio’s Nuton unit is trialling.

“Historically, low-grade ore bodies had very low recovery rates. Our technology teams have found a solution where we can achieve double the industry standard,” he said.

As global competition for dwindling copper resources grows more fierce, cash-rich companies, including Glencore and Newmont, have been targeting growth through aggressive M&A strategies.

But Barton, formerly a global executive at consultancy McKinsey, warns companies cannot rely on M&A alone to expand their copper operations. More creative thinking is needed longer-term.

“When you look at that pretty significant gap in demand versus supply . . . buying other companies is not going to solve that problem. You’ve got to find it,” he said.

On the exploration front, the Rio chair stresses the need to consider an increase in spending.

He also wants closer collaboration with smaller companies that typically carry out the early stage, higher-risk mapping and drilling that paves the way for the bigger groups to extract.

Another mining convention that needed challenging, he added, was Rio’s focus on large mining operations that were consequently among the 25 per cent lowest-cost producers, known as the first quartile mines.

“I still think the focus should be ‘first quartile’. But what about small? We can make them run pretty well, and then sure enough, you typically find more,” Barton said.

An additional problem in developing countries, highlighted by Mongolia’s Oyu Tolgoi project, is the pressure governments put on companies to develop processing facilities at mining sites, which could prove costly.

The Mongolian government wants Rio to build a copper smelter adjacent to Oyu Tolgoi, which the company is reviewing.

But Rio chief executive Jakob Stausholm hinted the economics of copper processing at the mine, including challenges around energy and water sources, mean it is unlikely to form part of its near-term plans.

“We will go far to try to solve things to the satisfaction of governments and societies. But of course, it also has to be profitable,” he said.

Credit: Source link