Moldovans have voted by a razor-thin majority to push ahead with talks to join the EU, results on Monday showed, marking an upset for President Maia Sandu, who had hoped to secure resounding backing for her policy of closer integration with Europe.

The landmark referendum asked voters whether the country’s constitution should change to enshrine a commitment to joining the EU after Moldova applied for membership in 2022.

Sandu had cast the referendum as a historic choice for the former Soviet nation between integrating more closely with the west and returning to the Russian fold.

Preliminary results on Monday showed it had passed by 50.38 per cent after ballots were counted by 99.37 per cent of polling stations — a surprisingly slim win by just 11,300 votes out of 1.5mn cast.

Polls had previously shown a substantial majority in Moldova — one of the poorest countries in Europe, sandwiched between Romania and Ukraine — to be supportive of the idea of joining the EU.

Sandu’s government applied for membership shortly after the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. The EU welcomed its bid and began accession talks earlier this year, pledging a €1.8bn multiyear package to help Moldova on the accession path.

But there was no obligation for Sandu to call the referendum at this stage in the process and some western officials described the move as a risky gamble based on overconfidence.

In a presidential election held the same day, Sandu also did not secure an outright victory. The race will now be decided by a second-round run-off on November 3 when Sandu will face her main rival Alexandr Stoianoglo, whose candidacy has been backed by the pro-Russia Socialist party.

Speaking to reporters at her election headquarters as results began to come through on Sunday night, Sandu decried an “unprecedented assault” on the democratic process by “foreign forces”.

For weeks before polling day, Moldovan authorities issued warnings about intense Russian interference, describing a fight against a hydra-like network of Kremlin proxies and an onslaught of illegal money intended to buy votes.

Law enforcement authorities estimated that Russia had spent about $100mn on influence operations and voter bribery, using funds brought in by “money mules” arriving on passenger flights from Moscow with substantial amounts of cash.

That network was deployed quite effectively on election day, one security official said.

Sandu said her government had evidence that “criminal groups” had “aimed to buy 300,000 votes” to sway the results. “Working together with foreign forces hostile to our national interests, [they] have attacked our country with tens of millions of euros, lies and propaganda,” Sandu said. “We will not back down.”

The Kremlin has previously denied any meddling in Moldova’s elections and accused Sandu of suppressing pro-Russia political views in the country.

On Monday, Kremlin spokesperson Dmitry Peskov depicted the results of the referendum vote as suspicious, claiming the number of votes in favour of Sandu and EU accession rose “mechanically” and “with anomalies”. He provided no evidence to support the claim.

Still, Russia is likely to view the outcome as something of a win, as it can capitalise on the closeness of the results to try to delegitimise the referendum and generally stoke divisions in the country, analysts said.

“We are entering the most vulnerable and turbulent period,” said Vladislav Kulminski, a former deputy prime minister of Moldova.

“The country is caught in the middle of a geopolitical tug of war where external players are pulling in different directions. And Moldova is very evenly divided, it turns out, between these competing vectors,” Kulminski said. “This is a classic recipe for potential disaster.”

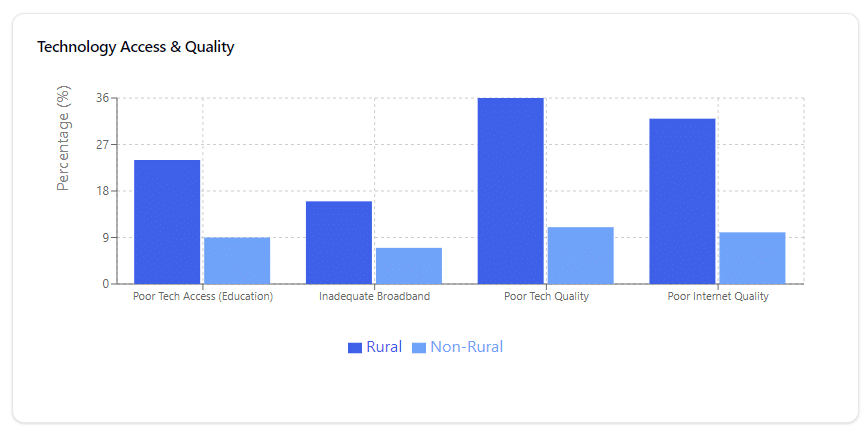

The election revealed the extent to which opposition to both Sandu and the EU appears to have been concentrated in rural and ethnic minority areas of the country, a source of division and one that Russia has previously sought to exploit.

Just 5 per cent of voters in Gagauzia — a small region in southern Moldova that declared itself independent after the fall of the Soviet Union but then accepted autonomous status within the country — voted in favour of the EU, the preliminary results showed.

Many of the votes that finally tipped the balance in favour of EU membership came in at the very end of the count from polling stations located abroad, leading some to question a result seemingly secured by the large Moldovan diaspora living in the west.

In the presidential race, Sandu landed 42 per cent of the vote, winning more votes in total than she did during her first-round run in 2020 against Igor Dodon.

However, her main opponent, Stoianoglo — a former prosecutor-general and relative political newcomer born in Gagauzia, whose candidacy has been supported by Dodon’s socialists — secured 26 per cent of the vote, which means they will now face off in a second round.

“It’s going to be a very, very close race,” said Kulminski, particularly if other minor candidates now throw their weight behind Stoianoglo. “The important thing is that the referendum passed, eventually . . . and that will not and cannot be ignored by whoever who wins the presidency.”

Sandu on Monday called on voters to back her in the run-off, which she depicted as a battle to “ensure these efforts were not in vain”.

The result in the presidential election will be critical not just for her political future, but also for a parliamentary vote next year which looks unlikely to yield a majority for Sandu’s party. An anti-EU majority in these could block reforms necessary for membership.

Additional reporting by Max Seddon in Riga

Credit: Source link